Introduction | Life | Work | Books

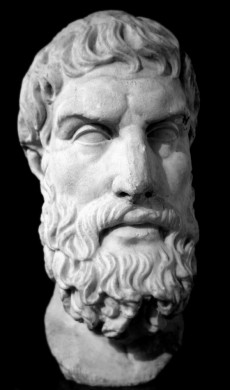

Epicurus

(Roman copy of Greek original marble bust, 3rd or 2nd Century B.C.)

|

|

Epicurus (341 - 270 B.C.) was a Greek philosopher of the Hellenistic period. He was the founder ancient Greek philosophical school of Epicureanism, whose main goal was to attain a happy, tranquil life, characterized by the absence of pain and fear, through the cultivation of friendship, freedom and an analyzed life. His metaphysics was generally materialistic, his Epistemology was empiricist, and his Ethics was hedonistic.

Elements of his philosophy have resonated and resurfaced in various diverse thinkers and movements throughout Western intellectual history, including John Locke, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, Thomas Jefferson (1743 - 1826) and the American founding fathers, and even Friedrich Nietzsche.

Epicurus was born in February 341 B.C. on the island of Samos in the Aegean Sea (off the Ionian coast of Turkey). His parents, Neocles and Chaerestrate were both citizens of Athens, but had emigrated to the Athenian settlement of Samos some ten years earlier.

As a boy, he studied philosophy under the Platonist teacher Pamphilus for about four years. At the age of 18, he went to Athens for his two-year term of military service. In the meantime, his parents were forced to relocate from Samos to Colophon in Ionia after the death of Alexander the Great, and Epicurus joined his family there after the completion of his military service.

He studied for a time under Nausiphanes, himself a pupil of the Skeptic Pyrrho, but by then a keen follower of the Atomism of Democritus. However, he found Nausiphanes an unsatisfactory teacher and later abused him in his writings, and claimed to be self-taught. He taught for a couple of years (in 311 - 310 B.C.) in Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, but apparently caused unrest and was forced to leave. He then founded a school in Lampsacus (on the Hellespont, modern-day Turkey) before returning to Athens in 306 B.C.

In Athens, Epicurus founded The Garden, a school named for the garden he owned that served as the meeting place of his Epicurean school, situated about halfway between the Stoa of the Stoic philosophers and the Academy of the Platonists. During his lifetime, his school had a small but devoted following, including Hermarchus, Idomeneus, Leonteus, Themista, Colotes, Polyaenus of Lampsacus, and Metrodorus of Lampsacus (331 - 277 B.C., the most famous popularizer of Epicureanism). It was the first of the ancient Greek philosophical schools to admit women (as a rule rather than an exception). With its emphasis on friendship and freedom as important ingredients of happiness, the school resembled in many ways a commune or community of friends living together, although, Epicurus also instituted a hierarchical system of levels among his followers, and had them swear an oath on his core tenets.

Epicurus never married and had no known children. He suffered from kidney stones for some time, and eventually died, in 270 B.C. at the age of 72, as a result of these stones and of a case of dysentery. Despite his prolonged pain, he remained cheerful to the last, and his final concerns were for the children of his student, Metrodorus.

After his death, communities of Epicureans sprang up throughout the Hellenistic world, and represented the main competition to Stoicism until its eventual decline with the rise of Christianity.

Epicurus is supposed to have written over 300 books, but the only surviving complete works that have come down to us are three letters and two groups of quotes, which are to be found in the "Lives of Eminent Philosophers" of the 3rd Century historian, Diogenes Laertius, and which present his basic views in a handy and concise form. Other evidence comes from the ruined town of Oenoanda, where the rich Epicurean follower Diogenes of Oenoanda had Epicurus' entire philosophy of happiness inscribed on the stones of the town's stoa in the early 2nd Century AD. Also, numerous fragments of his thirty-seven volume treatise "On Nature" have been found among the charred remains at Herculaneum. However, our two most important sources are reconstructions by the Roman poet and Epicurean Lucretius (c. 94 - 55 B.C.) and the Roman politician Cicero (although the latter was generally hostile toward Epicureanism).

Despite his insistence to the contrary, Epicurus was clearly influenced by the Atomism of Democritus, believing that the fundamental constituents of the world were indivisible little bits of matter (atoms) flying through empty space, and that everything that occurs is the result of the atoms colliding, rebounding and becoming entangled with one another, with no purpose or plan behind their motions (although, unlike Democritus, he did allow for possible "swerves" in their paths, which allowed for free will in an otherwise deterministic theory).

The philosophy of Epicureanism was based on the theory that the moral distinction between good and bad derives from the sensations of pleasure and pain (what is good is what is pleasurable, and what is bad is what is painful). Thus, moral reasoning is a matter of calculating the benefits and costs in terms of pleasure and pain. Unlike the common misconception that Epicureanism advocated the rampant pursuit of pleasure, its goal was actually the absence of pain and suffering: when we do not suffer pain, we are no longer in need of pleasure, and we enter a state of perfect mental peace (or ataraxia), which is the ultimate goal of human life. He therefore emphasized minimizing harm and maximizing happiness of oneself and others, and explicitly warned against overindulgence because it often leads to pain.

Epicurus himself followed his practical philosophy in his own life: his house was very simple, his clothes basic and his diet largely limited to bread, vegetables, olives and water. Simple Epicurean communities, based on The Garden, were established all across the ancient world, and his philosophies were popular for over 400 years.

Unlike the Stoics, Epicurus showed little interest in participating in the politics of the day, since doing so usually leads to trouble. He instead advocated seclusion: getting through life without drawing attention to oneself, without pursuing glory or wealth or power, but rather anonymously, enjoying the little things like food, the company of friends, etc. He counseled that having a circle of friends you can trust is one of the most important means for securing a tranquil life, and that "a cheerful poverty is an honorable state". In many ways, his Garden can be compared to modern communes.

The foundation of Epicurus' Ethics is the Ethic of Reciprocity (or the Golden Rule), which simply means "treat others as you would like to be treated", arguably the basis for the modern concept of human rights. He introduced into Greek thought what was then the radical concept of fundamental human Egalitarianism (he regularly admitted women and slaves into his school). He was also one of the first to explicitly endorse the idea of a social contract (that justice comes from a joint agreement not to harm each other - see the section on Contractarianism), developed much later by Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau, and the origins of Utilitarianism are often traced back to Epicurus.

He was also one of the first Greeks to break from the god-fearing and god-worshipping tradition of the time, and he caused something of a stir by claiming that the gods do not concern themselves at all with human beings (although he did affirm that religious activities are useful as a way to contemplate the gods and to use them as an example of the pleasant life). He strongly believed that death was not to be feared, because all sensation and consciousness ends with death, and so in death there is neither pleasure nor pain.

Epicurus also formulated a version of the problem of evil, often referred to as the Epicurean Paradox, questioning whether an omnipotent, omniscient and benevolent god could exist in a world that manifestly contains evil (see the section on the Philosophy of Religion). This was not aimed at promoting Atheism, but was just part of his overarching philosophy that what gods there may be do not concern themselves with us, and thus would not seek to punish us either in this or in any other life.

Epicurus is a key figure in the development of science and the scientific method because of his insistence believing nothing except that which can be tested through direct observation and logical deduction. Many of his ideas about nature and physics presaged important scientific concepts of our time.

See the additional sources and recommended reading list below, or check the philosophy books page for a full list. Whenever possible, I linked to books with my amazon affiliate code, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Purchasing from these links helps to keep the website running, and I am grateful for your support!

|

|