Introduction | Life | Work | Books

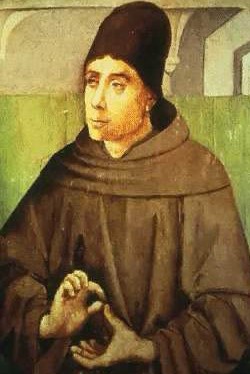

John Duns Scotus

|

|

John Duns Scotus (often known simply as Duns Scotus) (c. 1266 - 1308) was a Scottish philosopher and Franciscan theologian of the Medieval period.

He was one of the most important Scholastic theologians of the High Middle Ages, along with St. Thomas Aquinas, William of Ockham and St. Bonaventure (1221 - 1274), and the founder of a special form of Scholasticism, which came to be known as Scotism. He was also an early adopter of the doctrine of Voluntarism.

He was nicknamed Doctor Subtilis for his penetrating and subtle manner of thought, and had considerable influence on Roman Catholic thought. In the 16th Century, however, he was accused of sophistry, which led to the use of his name (in the form of "dunce") to describe someone who is incapable of scholarship.

Scotus was probably born around 1266 in the town of Duns in the Borders region of southern Scotland (“Scotus” simply means “the Scot”).

Very little is known of his life for sure. When he was a boy he joined the Franciscan order, and was sent to study at Oxford, possibly in 1288. We know that he was ordained as a priest in Northampton in 1291, and that he obtained his license to hear confessions at Oxford in 1300. He probably completed his Oxford studies in 1301 but, rather than remain as a master at Oxford, he was sent to the more prestigious University of Paris.

In the autumn of 1302, he began lecturing on Peter Lombard's "Sentences" (the set of opinions on Biblical passages which were often used as a springboard for discussions among Medieval scholars) at Paris. Later in that academic year, however, he was expelled from the University (along with several other papists) for siding with Pope Boniface VIII in his feud with Philip the Fair (King Philip IV) of France over the taxation of church property. He probably spent this time in exile back in Oxford (or possibly Cambridge), where he may have taught William of Ockham at some point. However, he returned to Paris before the end of 1304 (after Pope Boniface had died and the new Pope, Benedict XI, had made his peace with Philip).

He completed his Parisian studies, probably in early 1305, and was incepted as a master, and continued lecturing there until 1307. For reasons which still remain mysterious, he was dispatched to the Franciscan house of studies at Cologne, Germany, in October of 1307.

He died in Cologne on 8 November 1308, and was buried in the Church of the Minorites (an old unsubstantiated tradition holds that Scotus was actually buried alive following his lapse into a coma). His sarcophagus bears the Latin inscription: "Scotia me genuit. Anglia me suscepit. Gallia me docuit. Colonia me tenet" ("Scotland brought me forth. England sustained me. France taught me. Cologne holds me."). He was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1993.

Scotus was a great champion of St. Augustine and, like St. Bonaventure (1221 - 1274) and St. Thomas Aquinas before him, he wanted to reconstruct the thought of St. Augustine and Aristotle for the glory of God. But, although he had much in common with the other Scholastics of the time, he was not a mechanical repeater of any of them and he maintained several specific disagreements with them (and with St. Augustine himself).

Unlike St. Thomas Aquinas, Scotus rejected the distinction between essence and existence, denying that we can conceive of what it is to be something, without conceiving it as existing. Also in contrast to St. Thomas Aquinas, Scotus, believed in the controversial doctrine of univocity, that certain predicates may be applied with exactly the same meaning to God as to his creatures (Aquinas insisted that only analogical predication was possible, in which a word as applied to God has a meaning different from, although related to, the meaning of that same word as applied to creatures). Scotus also argued in favor of the doctrine of the immaculate conception of Mary (the great philosophers and theologians of the time were hopelessly divided on the subject, with Aquinas, for example, generally denying the doctrine).

In contrast to the later William of Ockham, Scotus is generally considered to have been a Realist rather than a Nominalist, in that he treated universals as real. However, he recognized the need for an intermediate distinction (that was not merely conceptual, but not fully real or mind-dependent either), resulting in his concept of a "formal distinction" (e.g. entities are inseparable and indistinct in reality, but their definitions are not identical).

His causal argument for the existence of God (of which he offered several versions), is perhaps the most complicated of any ever written, and constitutes a philosophical tour de force, despite its flaws. First he proved what he called the "triple primacy" (that there is a being that is first in efficient causality, in final causality and in pre-eminence); then he proved that these three primacies are co-extensive (i.e. any being which is first in one of these ways will necessarily also be first in the other two); then he proved that any being enjoying the triple primacy is endowed with intellect and will, and that any such being is infinite; and finally he proved that there can only be one such being.

Scotus devised perhaps the earliest formulation of Voluntarism (the view that regards the will is the basic factor, both in the universe and in human conduct), emphasizing the divine will and human freedom in all philosophical issues.

See the additional sources and recommended reading list below, or check the philosophy books page for a full list. Whenever possible, I linked to books with my amazon affiliate code, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Purchasing from these links helps to keep the website running, and I am grateful for your support!

- Duns Scotus - Philosophical Writings: A Selection 2nd Edition(PB) Edition

by John Duns Scotus (Author), Allan B. Wolter (Translator), Marilyn McCord Adams (Foreword)

- The Cambridge Companion to Duns Scotus (Cambridge Companions to Philosophy) Edition Unstated Edition

by Thomas Williams (Editor)

- Duns Scotus on the Will and Morality

by John Duns Scotus (Author), William A. Frank (Editor), Alan B. Wolter (Translator)

- Duns Scotus (Great Medieval Thinkers) 1st Edition

by Richard Cross (Author)

- Duns Scotus, Metaphysician (Purdue Studies in Romance Literatures) (Purdue University Press Series in the History of Philosophy)

by William Frank (Author), Allan B Wolter (Author)

- Five Texts on the Mediaeval Problem of Universals: Porphyry, Boethius, Abelard, Duns Scotus, Ockham

by Paul V. Spade (Translator)

|

|